Servadio the Shaman

On a massage table he laid, rigid as a corpse, dressed only in chinos and trainers as a camera hovered above his eye-line, focused on his chest. A shoji screen shielded his feet as a student-flat party of scenesters in black satin, denim, leather and lace, gathered around his neck swilling wine from disposal cups, eager for the composer of this Frankenstein-esque scene to begin his work. Outside, on Dalston Lane, east London, equal numbers dressed black as a funeral procession buzzed like moths beneath the Sang Bleu sign as they sucked back cigarettes on a Monday evening in late February. Holding a tattoo machine like a scalpel Michele Servadio began to mark his canvas of flesh as a rumbling soundscape searched for a rhythm and the screens reflected his work. Like a jackhammer the gun dislodged pigment, setting off car alarms like a thief in a car park, shattering brick walls and whipping the air into gale force winds as the subject’s father edged through the crowd: “Sorry, that’s our son… I’m just wondering what they’re doing to him”, he offered, apologetically, as his boy became an instrument of industrial sound.Reaching a Mad Max climax the images on the screen reverberated as Servadio dug deeper, as if sawing-open the sternum with an angle grinder, fracking for his subject’s soul, as sonar sounds echoed and the procedure ricocheted across a dozen iPhone screens. Black rubber gloves smear black ink across the subject’s chest like a finger painting as the music climbs the high canopies of consciousness into metaphysical recesses and dreamscapes. The boy’s chin is high, his throat soft as tissues, as Servadio stands above him examining his work – an abstract scribble. Silence gives way to howling applause as his subject stands, slight as spaghetti, and poses for pretty girls with fancy cameras and a pink-haired lad with a gold retro cell phone charm earring who secures his skateboard like a baguette under his arm as he steals a few digital keepsakes of the evening. The subject’s dad gives a thumbs-up as the skater retreats into the crowd and tries to impress a girl with talk of having his dick inked. Reaching a Mad Max climax the images on the screen reverberated as Servadio dug deeper, as if sawing-open the sternum with an angle grinder, fracking for his subject’s soul, as sonar sounds echoed and the procedure ricocheted across a dozen iPhone screens.

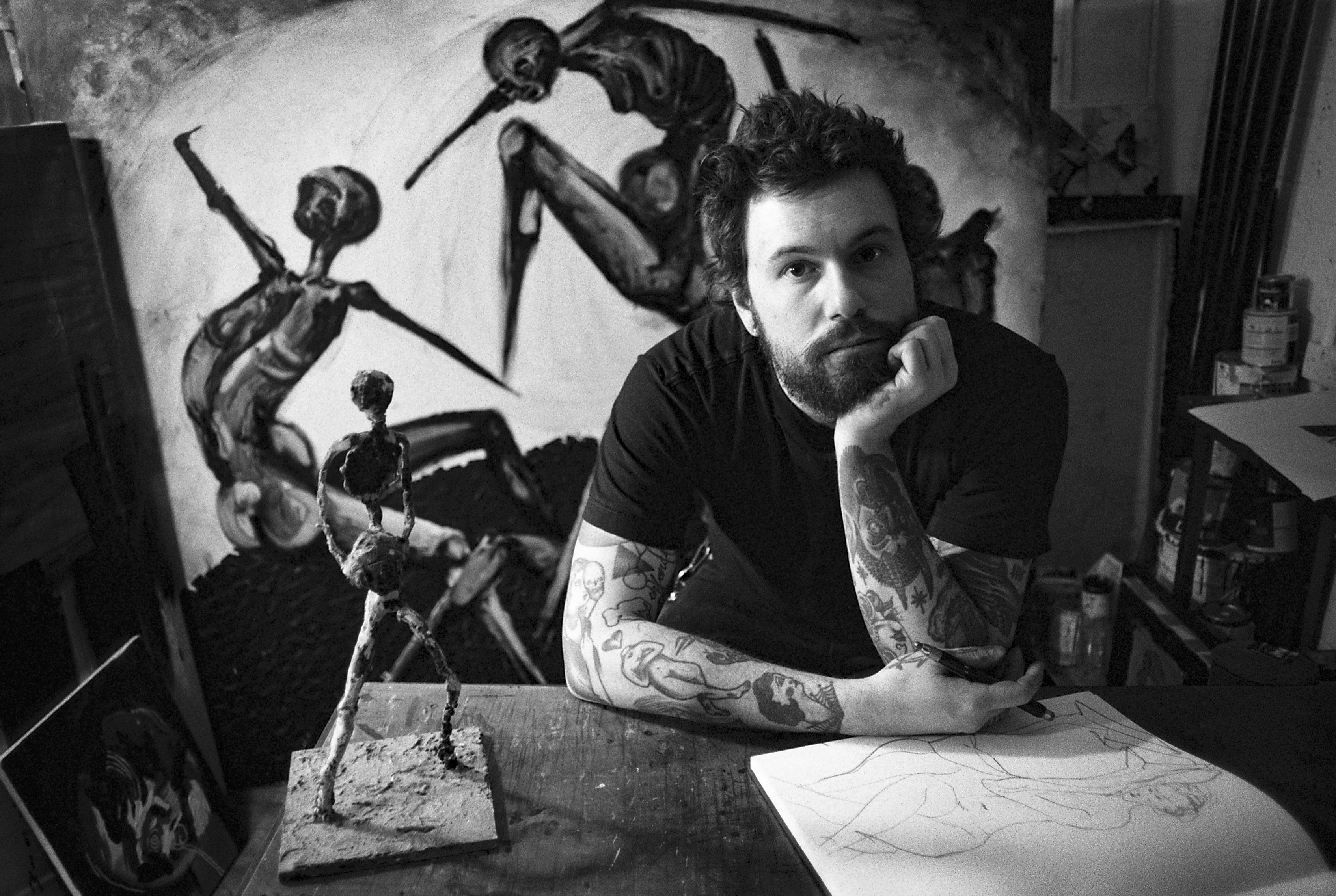

Black rubber gloves smear black ink across the subject’s chest like a finger painting as the music climbs the high canopies of consciousness into metaphysical recesses and dreamscapes. The boy’s chin is high, his throat soft as tissues, as Servadio stands above him examining his work – an abstract scribble. Silence gives way to howling applause as his subject stands, slight as spaghetti, and poses for pretty girls with fancy cameras and a pink-haired lad with a gold retro cell phone charm earring who secures his skateboard like a baguette under his arm as he steals a few digital keepsakes of the evening. The subject’s dad gives a thumbs-up as the skater retreats into the crowd and tries to impress a girl with talk of having his dick inked. Sang Bleu is a paradoxical place for Servadio to perform for he has not so much rebelled against the tattooing scene, for which the shop is a mecca, but ignored it altogether. Yet his installation – Body of Reverbs – the headline act of Maxime Plescia-Buchi’s latest project launch – TTTism, a contemporary tattooing Instagram vision realised in print – signifies his ascension and the mainstreaming of his mixed-medium exploration, which began in London with performances involving Sitex security screens – the metal sheets landlords ambitiously use to keep out squatters, which Servadio was for three years after packing a bag and his bike, to relocate, from his native Venice, in 2010. The decision was made on a whim, with a mate, having spent “three… maybe four years” at a visual arts school in Venice where he moved to escape the boredom of his hometown, a village called Arzergrande, and to develop his drawing, “the only thing I could do and the only thing I really enjoyed doing”. The course was “nothing academical”, but Servadio passed the time “mainly doing my own things… I’ve never been a good student”. He did illustrations for Punk bands, painted and skateboarded – the sport whose 80s’ skull and snake motifs – made famous by Powell Peralta’s Tony Hawk and Mike McGill – were the genesis of his early tattoo work. While initially thinking tattoos were “tacky”, Servadio nonetheless inked a jawbone on his own thigh age 20 or 21, before turning the gun on his friends. “As soon as I tried, I was like, ‘this is the thing. This is beautiful’. “Tattooing taught me to avoid what is not necessary. Minimal works.”